One could continue to comb through the Christian scriptures to locate every instance of the mention of “hell” or a related description, and drawing up a large list, sit down to examine what the NT really says about the subject. One must be sensitive to literary styles, the use of metaphor, poetry, etc, while at the same time acknowledging when a text seems to indicate its actors truly believe the topic of their discourse has definite characteristics, really existing in some sense. So, for example, when reading the following passage:

“We ought always to thank God for you, brothers and sisters, and rightly so, because your faith is growing more and more, and the love all of you have for one another is increasing. Therefore, among God’s churches we boast about your perseverance and faith in all the persecutions and trials you are enduring.

All this is evidence that God’s judgment is right, and as a result you will be counted worthy of the kingdom of God, for which you are suffering. God is just: He will pay back trouble to those who trouble you and give relief to you who are troubled, and to us as well. This will happen when the Lord Jesus is revealed from heaven in blazing fire with his powerful angels. He will punish those who do not know God and do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus. They will be punished with everlasting destruction and shut out from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of his might on the day he comes to be glorified in his holy people and to be marveled at among all those who have believed. This includes you, because you believed our testimony to you.

With this in mind, we constantly pray for you, that our God may make you worthy of his calling, and that by his power he may bring to fruition your every desire for goodness and your every deed prompted by faith.” (2 Thessalonians 1:3-11)

It should be obvious that hell, i,e, “punishment with eternal destruction” functions in a number of ways: 1) As a promise that wrongs will be righted, that in the end there will indeed be justice for those followers of Christ who suffer terribly at the hands of their persecutors, proving the validity of the statement “God is just.” It goes without saying that, based on this passage, God’s justice is contingent on his being able to punish those who cause such “suffering” (1:5). In other words, calling into question God’s lack of mercy or grace for the persecutors simultaneously calls into question his justice.

2) This promise of eternal punishment for the persecutors brings hope to the persecuted. It is obvious that it is here meant as an encouragement for those Christians who are suffering. It functions as a reminder of their calling from God.

3) The writer contrasts two types of judgment: a) God’s judgment in his calling, and b) God’s judgment against those who persecute his elect. It seems clear the writer believes God has chosen (judged) some to be faithful in Thessalonica, that he has chosen beforehand who will be called. For some this is offensive to our modern sensibilities (does God not love all, why not call all?), whereas for others of a more Calvinist strand it is merely an indication of God’s sovereignty (the debate is ancient, again due in large measure to scripture’s ambiguities/inconsistencies). That the Thessalonican’s perseverance is “evidence that God’s judgment is right” (he chose wisely beforehand, somewhat like when we were children and chose a soccer team from among our classmates who later proved victorious- this is precisely what is happening with Job: Satan calls into question God’s judgment that Job is righteous, the rest of the story unfolds with the vindication of Job and therefore God himself. This is why I believe the introduction with Satan is a vital part of the text), so too will his judgment righteously fall upon those who oppose his chosen, a positive and a negative judgment.

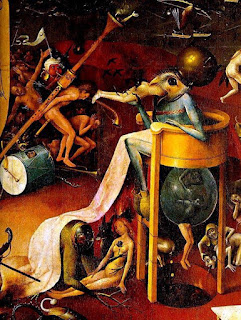

4) That hell as eternal punishment is a real possibility, that it involves both fire and absence from God, i.e. it’s not merely metaphorical but actually descriptive. The writer really believes it will “happen this way” and encourages his listeners to believe “this will happen” (1:7).

I’m sure it is possible to further examine this passage in light of other critical approaches, to further flush out the life world of his audience (sociological/anthropological), to investigate further his descriptive terminology from a historical perspective (archaeological/literary) etc.

All of this is merely the scriptural consideration. Within a certain Christian approach this is sufficient. But for a large number of Christians, tradition also plays a vital role: “What has the Church to say about this topic?” Not just the Church right here in the particularity of our little town or city, but what has the Church, that great mass of saints spanning two thousand years, those great councils, those men and women of great learning and devotion, what have they to say? Can they so easily be dismissed with the naive statement “speak where the Bible speaks, be silent where it is silent”? It should be obvious how impossible this task is, how unproductive and confusing, how divisive in the long run.

We have not yet come to the end of our explorations.